Health Activism: from citizenship to radical care

“An indigenous person in Chile is born with stigma and discrimination – if we add Aids, there is a double discrimination”

Willy Morales, president of RENPO

Lampa, August 2016

In October 2015, I attended the first “Futa Trawun Che, kutran VIH/SIDA” (Large meeting of indigenous peoples who are ill of HIV/Aids) held at the Mapuche indigenous health center “Meli Lawen Lawentuchefe” in Lampa, Chile. The meeting was organized by Red Nacional de Pueblos Originarios en Respuesta al VIH/Sida (RENPO) – National Network of Original Peoples in Response to HIV/Aids in English. Following the indigenous protocol, the meeting opened with a ceremony that included greetings and acknowledgments to the spiritual leaders, past and present, and setting the intention to bring well-being to those present. Representatives from Lampa municipality, the Chilean Ministry of Health, the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), and the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) also participated in this meeting and introduced themselves. I was surprised to see them actively listening to the words of Willy Morales, the president of RENPO, who narrated his struggles as an indigenous diagnosed HIV patient.

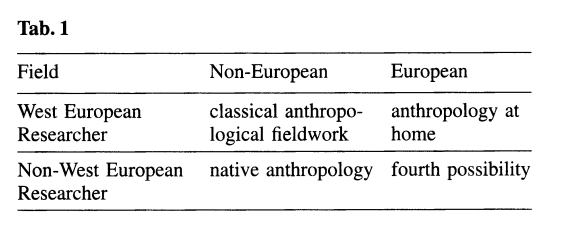

After completing my doctorate, I returned to my home country and began my postdoctoral position. At the time, I was focusing on patients’ organizations in Bolivia (Saravia 2019, 2015) and had just started exploratory research about the role of patients’ organizations in generating new legislation in Chile. In this precarious context, Foucault’s theoretical framework of biopolitics and the concept of biological citizenship, as proposed by A. Petryna (2013), appealed to me. I thought these perspectives would help me to understand the sociopolitical dynamics and the subjectivities that emerged through the work of indigenous and non-indigenous patient activists and advocates who navigate the precarious spaces of neoliberalism. However, after listening to the indigenous leaders presenting at the meeting and their work in pushing for changes at the national level that could help access culturally informed treatment and more accessible testing for HIV, I began to question whether the political engagements were just about reclaiming rights and what was the content of the relationships being built within RENPO. Since then, I have become an advocate for this organization and have collaborated with them throughout the years.

In this short essay, I examine the work of RENPO, an indigenous organization of patients and advocates, as an example of collective care that disrupts current notions and structures of political engagement in health education and activism. Historically, coloniality has placed indigenous movements at the margins of health policymaking. However, RENPO is shifting that reality through local and community-based actions and influencing the discourse on HIV prevention and control in Chile.

My friend and colleague Jorge Tibor Gutierrez, whom I met during my undergraduate training in anthropology, had shared with me some of his experiences working along an organization of indigenous peoples from diverse communities and peoples all along Chile, including the Aymara, Rapa Nui, Mapuche, and Huilliche. RENPO had been organizing several advocacy campaigns, including one led by the International Labor Organization (ILO) in 2010 related to the education of truck drivers, who are particularly vulnerable to HIV infection. RENPO assisted the ILO with HIV information materials written in indigenous languages and developing “The Road to Respect” education manual.

RENPO was formally constituted as a non-profit “corporacion” (civil association) in 2012, and their name was “Encuentros de Vida” (my translation: “Life Gatherings”). Their mission is guided by the principle of health and healthy life, preventing and curing catastrophic illnesses that affect persons and their environments. With this holistic goal, the association started working closely with the Ministry of Health, organizing campaigns and assisting the intercultural health program and other health interventions beyond infectious diseases. In their way of responding to the HIV pandemic, RENPO has developed several strategies, some of which I was able to observe firsthand as part of our collaboration these past seven years.

Health Activism as Radical Care

Besides the formal meetings with health authorities, conferences, and international alliances with other Latin American Indigenous organizations (including a recent meeting with the Latin American coalition of Indigenous Peoples in November of 2023), most of the work of RENPO focuses on nurturing indigenous knowledge and embodied practices at the local level. The healing center in Lampa, attached to a public primary care clinic, is at the core of RENPO’s everyday forms of care. Ruth Antipichun, one of the founding members of RENPO, leads the healing center as a Lawentuchefe (Mapuche herbalist), performs healing rituals, and prepares educational sessions and training for local non-indigenous providers and students. Ruth Antipichun and her team of intercultural facilitators care for the medicinal garden adjacent to RENPO’s community center and concoct the required plant-based treatments. At the Meli Lawen Lawentuchefe Center, Ruth performs what anthropologists have referred to as care as processes of world-making and engagements with the world of medicine that includes more-than-human agents (de la Bellacasa 2017, 2010). Ruth’s care work connects to the rest of RENPO’s entanglements of care for each other, for example, holding listening sessions during meetings where members share experiences and emotional responses to failures or successes in their work. For many members, the organization has helped them reconnect with their indigeneity, as one man told me, “Now, I can dress like a Mapuche man and speak my language proudly; I could not do that before” (Santiago, June 2018). In this sense, through continuous and cohesive social actions, RENPO also disrupts established definitions of patients’ organizations or even what is understood as an indigenous organization. The fact that RENPO and its members identify themselves in response to the HIV pandemic is also evidence of their willingness to produce a change in how public health officials see indigenous peoples in Chile.

Moreover, at the core of it all, using Murphy’s (2015) framing of decolonizing care, there is an explicit indigenous intention and understanding of how to care. In contrast to hegemonic racialized and authoritarian framings in which indigenous health initiatives operate, RENPO actively unsettles such framings of care by connecting relationships of care for indigenous HIV/Aids patients to other claims for community well-being, such as sustainable food systems and environments. One example was the role of RENPO activism in Chiloé during the toxic red tide event of 2016, where its leaders played an important role in the broader social movement against salmon farming industries-driven environmental crises and Chile’s permissive legislation that allows unchecked ecological disasters.

In their 2020 essay, Hobart and Kneese argue that we should think of care as part of social movements and collective strategies that provide hope (possibilities) in precarious contexts. Thinking about the therapeutic landscape built by RENPO in Lampa, as well as the solid alliances and coalitions built throughout Chile and beyond, a concept of radical care provides more substantial ways of understanding RENPO’s political work.

In this short essay, I have described the work of RENPO as a way to unsettle our understanding of indigenous health activism, seeing collective action as radical care that has been crucial in negotiating alternatives for reclaiming and de-centering biomedical models of care.

Acknowledgements

This work would not be possible without the generosity of RENPO’s leaders and members in sharing their experiences and knowledge with me. I especially thank Willy Morales, Ruth Antipichun, Elba Huinca Meliñir, Doraliza Millalen, and Jorge Tibor Gutierrez.

Paula F. Saravia studied social anthropology at Universidad de Chile (1995-2000), where she specialized in medical anthropology. She worked on poverty reduction programs in Chile and taught at Universidad de Chile as a Lecturer. In 2006, she received an Erasmus Mundus grant from the European Union to study in the interdisciplinary Master’s program “Phoenix Dynamics of Health and Welfare.” Her dissertation research focused on understanding modes of engagement and tuberculosis illness experiences within Aymara communities in Bolivia and Chile. Her current research is oriented toward understanding the mental health impact of environmental precarity among indigenous communities in Northern Patagonia, Chile. She joined the Department of Anthropology at the University of Washington in June of 2021 and is currently an Assistant Teaching Professor in Medical Anthropology and Global Health.

References

de La Bellacasa, Maria Puig. Matters of care: Speculative ethics in more than human worlds. Vol. 41. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

de La Bellacasa, Maria Puig. 2011. Matters of care in technoscience: Assembling neglected things. Social studies of science, 41(1), 85-106.

Hobart, Hi’ilei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani and Tamara Kneese. 2020. “Radical Care: Survival Strategies for Uncertain Times.” Social Text 38 (1), p.1-16

Murphy, Michelle. 2015. “Unsettling Care: Troubling Transnational Itineraries of Care in Feminist Health Practices.” Social Studies of Science 45 (5), p. 717–737.

Saravia, Paula F. “Tuberculosis, involucramientos políticos y espacios biosociales en Bolivia.” estudios atacameños 62 (2019): 297-310.

Saravia, Paula Francisca. Ujuk Usu. Medicine, Tuberculosis and Race among the Aymara of the border between Bolivia and Chile. University of California, San Diego, 2015.