This essay seeks to challenge the idea of evidentiary knowledge in anthropology and to critically examine in what ways anthropologists —particularly those working with physical and digital archival methods—make use of ethnographic materials rooted in conflict-laden contexts. Our cases from Palestine and the United States—suffering from continuous colonial practices, ongoing dispossession, and identity erosion— highlight how knowledge production is a core feature of racial regimes, and thus challenge the idea that these archival materials constitute a holistic source of evidentiary knowledge.

Emphasising the epistemological problem of the lack of balance in power, we call on anthropology—the discipline devoted to understanding human lives—to critically investigate the prevailing conception of evidentiary knowledge, and instead of perceiving archives solely as repositories of evidentiary knowledge based on the presence and availability of materials, anthropologist should seriously consider absences, erasures, and silences in these same sites. This understanding, we argue, enables anthropologists to reread colonial archives ‘against their grains’, as Ann Stoler (2002) suggests. Thus, rather than normalising the archive in a way that maintains the status quo, anthropologists can transform it into a site of resistance, allowing change over time and joining ongoing scholarly efforts to establish decolonial archives.

The Establishment of Israeli Archives and the Destruction of Palestinian Archives

Since Israel’s establishment in 1948, it has continued to be increasingly preoccupied with creating and developing its archives. Most renowned among these efforts is its extensive police and military archives. The Israel Defense Forces’ (IDF) Archive is the main historical archive of the Israeli military, established in 1948, serving Israel’s Defense Ministry and the IDF as a storage centre for their daily work, research, and legal purposes, and includes valuable files related to Palestine (Cohen 2011). Israel is also known for its national library archive (NLI), not only notable for its cultural treasures of Israeli and Jewish heritage collection, but also for its extensive Islamic and Middle East collection (Blumberg & Ukeles 2013), and while perceived by some as facilitating the flow of knowledge, others were nonetheless suspicious of it (e.g., Othman 2017), focusing on what is missing and erased from it.

Along with establishing its own archives, Israel has devoted substantial efforts to destroying Palestinian archives (Desai & Shahwan, 2022; Sela, 2018; Sleiman, 2016). The Great Book Robbery, a documentary film, explores Israel’s looting of 70,000 Palestinian books from private Palestinian libraries during the 1948 war, and shows that 6,000 of these books are now marked as ‘AP’–Abandoned Property. By trying to understand why thousands of books appropriated from Palestinian homes are still in the NLI, this documentary interweaves various storylines into a unified structure, portraying a story of a robbery, not of cultural preservation.

Israel was also responsible for the destruction of the Palestine Liberation Organization’s (PLO) archives in Beirut during the invasion of 1982, raiding the offices of the Palestine Research Center (PRC), confiscating and seizing the archives that had been established in 1965 to gather and conserve Palestinian materials (Sleiman 2016). Moreover, the IDF also took over the Palestinian Cinema Institute (PCI), including its professional film archive (Sela 2017). Currently, the films are managed and controlled by the IDF, which conceals much of the information about their origins (Desai & Shahwan 2022).

The academic interest in archives, their politics, and the ways in which they were established or destroyed in the context of Palestine has been increasing. Examining Israel’s colonial archives holding plundered Palestinian materials, Rona Sela (2018), for example, provides insights into Israel’s colonial mechanism of looting and truth production. By focusing on the archives plundered by Israel in Beirut, she traces how Israel looted Palestinian archives and then controlled the materials in its own colonial archives. Sela traces the repressive means in which Palestinian archives were erased , including censorship and various restrictions, as well as the ways in which Israel limited the exposure and the use of Palestinian looted materials, altered their original identity, regulated their contents, and subjected them to its laws and terminology.

Similarly, Hana Sleiman (2016) details the various systematic powers that tried to silence the PLO archive. Furthermore, she shows how the looted documents were used later by Israeli research institutions to create a narrative depicting the PLO as a ‘terrorist organization at the nexus of international rogue actors, emphasising its connection to the Eastern bloc, Arab and Islamic countries, and other countries that allow subversive groups to operate, like many countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America’ (49). Sleiman notes the irony behind Israel’s claim that its narrative is authentic because it is based on the PLO’s own documents and records. According to Sleiman, Israel’s claims to be fully faithful to the documents’ hidden script is simply putting into words the truth that the colonial archive is demanding.

Orouba Othman (2017) examines the ways in which the Palestinian historiography has been re-narrated to maintain Israeli hegemony, including its settler narratives. One example she brings is that while Palestinians have been depicted as simply having given up their spiritual and material possessions, the staff of the NLI has been portrayed as having risked their lives for these neglected documents. This imagery highlights what is conventionally considered the abyss between the Oriental, purportedly lacking the basic capacity to protect its culture, and the Western Zionist, always able to overcome obstacles. In this way, the moralistic-heroic Israeli narrative of the 1948 war was constructed, according to Othman.

Israel’s approach to archives, its long-standing national effort to build vast and detailed archives along with its policies, regulations, decisions regarding the release or lack of release of materials, and its constant attempts to destroy Palestinian archives, seems puzzling, perhaps even suspicious. Why are perpetrators of violence and those involved in conflicts so preoccupied with documenting and creating archives? Why do colonial archives tend to be very detailed archives? What might explain the tendency to restore and archive materials in this capacity? In which circumstances does Israel make the decision to keep its archival documents classified, censored, and out of reach? Conversely, in which circumstances does Israel decide to allow access to its archival documents, even leading initiatives and creating digital archives to enhance public access and knowledge?

The Censorship of Critical Race Theory Discourse

In the U.S., conservative popular media is abuzz with the term critical race theory (CRT) alongside aims to change and regulate the types of reading and content they deem inappropriate for discussions in schools and the workplace. Anti-CRT advocates claim these discussions, particularly within public schools, are harmful to the self-esteem of white children or introduce children to perspectives that parents may not share. They argue parents should have control over what their children learn and how. The term ‘critical race theory’ originated within legal academia as a starting point for acknowledging and analysing how racism is systemically embedded in U.S. law and legal practices (Bell 1992; Crenshaw et al. 1996; Delgado and Stefancic 2017). However, the term has been misappropriated through social media to discuss any direct or indirect inclusion of critical perspective suggesting racism exists and to brand this discussion illegitimate and inappropriate (Wallace-Wells 2021; Will 2021). Additionally, the term critical race theory is used as a catch-all to brand and restrict discussion about ‘Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion’ work, LGBTQ+ experiences, reproductive health, immigration, and alternative politics – ‘socialism, Marxism, communism, totalitarianism, or similar political systems’ – among other things deemed in conflict with ‘the principles of freedom upon which the U.S. was founded’ (Pendharker 2022). This suggests a kind of cultural anxiety (Grillo 2003: 158), whereby discussing racism, homophobia, and other controversial topics within education pushes against their fundamental sense of Americanness.

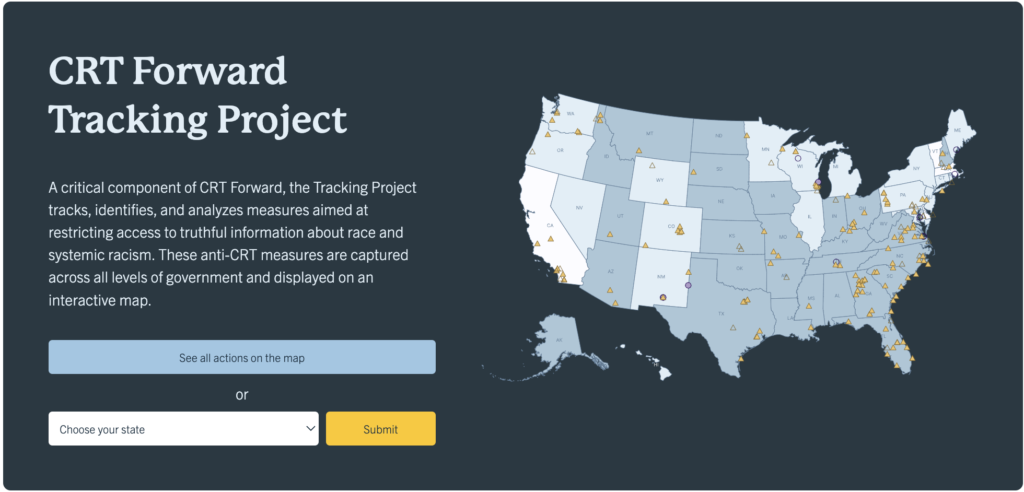

The misappropriation of the critical race theory and its circulation in online began during the COVID-19 lockdowns as a counter-discourse to the reignition of #BlackLivesMatter protests following the murder of George Floyd. The anti-critical race theory movement has moved from social media to attempts to regulate public education and workplace curriculums. The UCLA School of Law Critical Race Studies (CRS) Program launched the ‘CRT Forward Tracking Project’, which catalogues the various policy and legislation introduced to restrict the ability to create mandatory discussion or engagement from the local to national level with materials that suggests the U.S. has systemic racism or is misappropriated to restrict other diverse perspectives. The Project claims 20% of all proposed policies are introduced at the school district level (Sloan 2022). While this means school districts have more control over consideration of such complaints, there are real consequences for educators and students implicated in such complaints. Educators live in fear of being targeted individually and slandered online using the same misconstrued and inflammatory language that began this movement if they support retaining materials (texts, films, lessons, etc.) that depict experiences unpopular with the anti-CRT movement (First Person 2022; Waxman 2022). The parents of students of various backgrounds feel their children will not be exposed to relatable cultural representations or that may diversify how they understand the world and their relationship to it (Will 2021). The anti-critical race theory campaign attempts to censor what people can learn, share, and discuss while privileging the omission of materials that attempt to grapple with a messy national history that continues to reproduce inequality for many in the U.S.

These efforts echo the larger issues at stake with materials available to teach about diverse opinions and perspectives – the archive is already limited and shaped by colonialist values and anxieties. Stoler (2009: 3) discusses how exploring ‘the archive’ reveals the importance of documents and documentation, as they lend legitimacy and power and also illustrate the priorities of colonial powers and their institution of colonial rule as an economic, political, and legal reality. Archives also illustrate colonial ontologies, or how these colonial powers understood themselves and their ‘being’ and place in space, as distinct through the subjugation of groups of the ‘Other’ (Stoler 2009: 4; Stoler 2002: 6-8). Omission of materials created by groups of the ‘Other’ within ‘the archive’ or documentation outlining the extreme violence perpetuated against them, the nothingness or nonexistence it implies (Navaro 2020: 163), reduces the opportunity of introducing counternarratives that may undo the legitimacy and logics undergirding the continuance of colonial powers through subjugation as well as anticipated and actualized violence – a phenomenon that Stoler (2016) terms ‘duress’. Counternarrative was precisely the aim of those who coined the term critical race theory. Counternarrative also exists in the form of children’s and young adult literature or educational materials focused on the experiences or possible futures of those that have been historically Othered. These materials similarly unravel racism and colonialist logics in the public sphere, outside of legal academia, and create space for children or adults to muck through personal experiences of subjugation where they may lack the language to acknowledge the truth of its presence and impact in their lives.

Conclusion

The cases of Palestine and the United States offer a retrospective view that enables us to learn about the archive, its politics, and its influences. Both cases challenge the idea of the archive as an essential arena that can simply provide reliable information. It also demands that we pay attention to the role of colonial archives in shaping anthropological research, both methodologically and theoretically. Both the Palestinian and American cases show how political actors, perpetrators of violence, and victors in these contexts destroy narratives that threaten to undermine their legitimacy, narratives, discourses, and political interests. That is, our comparison highlights how knowledge production could be a core feature of conflict-laden contexts and racial regimes.

What production of knowledge processes should anthropology engage in to overcome the absences, erasures, silences, and ‘black holes,’ (Navaro 2020: 161) that could impact our research (Basu and De Jong 2016; Odumosu 2020)? And how should we capture these erasures ethnographically, without abandoning the idea of empiricism, the core of our ethnographic method? These questions are extremely salient in anthropology today due to the increasing incorporation of primary historical records in anthropological research and analysis, known as ‘the historical turn’, and the representation of settler-colonial relations, erasure of histories and narratives, cultural demolitions, conflict, and dispossessions within those records.

We contend that this critical view of the archive should be woven into anthropological training. In utilising an archive, whether physical or digital, a researcher must consider absence as significant to their analysis as what is present or dominant. The analysis should contemplate the implications of that absence of material as potentially constitutive of the material that is present. In some instances, such a view could call to question the fundamental legitimacy of the archive where material was sourced and may point to the impossibility of gathering certain information. Our aim is to advocate for an academic rebalancing in our disciplinary pedagogy, whereby decolonisation works through attention to and privileging the occluded and omitted perspectives and creations of the ‘Other’.

Adaiah Hudgins-Lopez is a writer, creative, and PhD Social Anthropology student at the University of Cambridge. She is a 2021 and 2022 Gates Cambridge Scholar and member of Trinity College.

Alaa Hajyahia is a Ph.D. student in social anthropology at the University of Cambridge. She is a 2022 Gates Cambridge Scholar and a member of King’s College.

References

Basu, P., & De Jong, F. 2016. Utopian archives, decolonial affordances. Introduction to Special Issue. Social Anthropology, 24(1), 5– 19. doi: 10.1111/1469-8676.12281.

Bell, Derrick. 1992. Faces at the Bottom of the Well: The Permanence of Racism. New York: Basic Books.

Blumberg, D., & Ukeles, R. 2013. The National Library of Israel renewal: Opening access, democratizing knowledge, fostering culture. Alexandria, 24(3), 1-16.

Cohen, H. 2011. Good Arabs: The Israeli security agencies and the Israeli Arabs, 1948–1967. Univ of California Press.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé, Neil Gotanda, Gary Peller, and Kendall Thomas. 1996. Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement. New York: New Press.

Delgado, Richard and Jean Stefancic. 2017. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, 3rd edition. New York: New York University Press.

Desai, C., & Shahwan, R. 2022. Preserving Palestine: Visual archives, erased curriculum, and counter-archiving amid archival violence in the post-Oslo period. Curriculum Inquiry. 52(4), 469-489.

First Person. 2022. ‘A Librarian Spoke Against Censorship. Dark Money Came For Her.’ https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/17/opinion/librarian-book-bans-freedom-of-speech.html

Grillo, Ralph. 2003. ‘Cultural Essentialism and Cultural Anxiety’. Anthropological Theory, 3(2), 157–173.

Navaro, Yael. 2020. ‘The Aftermath of Mass Violence: A Negative Methodology’. Annual Review of Anthropology 49: 161-73.

Odumosu, T. 2020. The crying child: On colonial archives, digitization, and ethics of care in the cultural commons. Current Anthropology 61(S22), S289-S302.

Othman O. 2017, December 13. ‘Jared: How do we deal with our stolen history?’ 7iber. https://www.7iber.com/politics-economics/jrayed-our-stolen-history/

Pendharker, Eesha. 2022. ‘Here’s the Long List of Topics Republicans Want Banned From the Classroom’. Education Week 41(23): 6+.

Sela, R. 2018. The genealogy of colonial plunder and erasure–Israel’s control over Palestinian archives. Social Semiotics, 28(2), 201-229.

———. (2017). Seized in Beirut: The plundered archives of the Palestinian Cinema Institution and Cultural Arts Section. Anthropology of the Middle East, 12(1), 83-114.

Sleiman, H. 2016. The paper trail of a liberation movement. The Arab Studies Journal, 24(1), 42-67.

Sloan, Karen. 2022. ‘UCLA Law Project Catalogs Hundreds of Anti-Critical Race Theory Measures’. https://www.reuters.com/legal/legalindustry/ucla-law-project-catalogs-hundreds-anti-critical-race-theory-measures-2022-08-03/

Stoler, Ann Laura. 2002. Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule. Berkeley: University of California Press.

———. 2009. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

———. 2016. Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times. Durham: Duke University Press.

UCLA Critical Race Studies Program. ‘UCLA Law CRT Forward Tracking Project.’ https://law.ucla.edu/academics/centers/critical-race-studies/ucla-law-crt-forward-tracking-project

Wallace-Wells, Benjamin. 2021. ‘How a Conservative Activist Invented the Conflict Over Critical Race Theory’. https://www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-inquiry/how-a-conservative-activist-invented-the-conflict-over-critical-race-theory

Waxman, Alicia. 2022. ‘Anti-‘Critical Race Theory’ Laws are Working. Teachers are Thinking Twice about How They Talk about Race’. https://time.com/6192708/critical-race-theory-teachers-racism/

Will, Madeleine. 2021. ‘Calls to Ban Books by Black Authors are Increasing Amid Critical Race Theory Debates; Parents claim books about race make white children feel uncomfortable.’ Education Week 41(10): 11+.